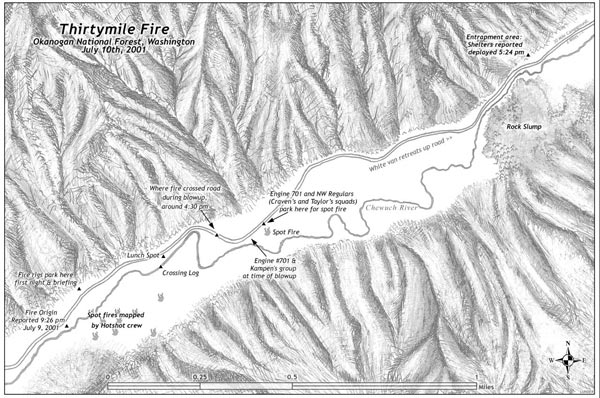

I got a call back in 2004 from John Maclean, author of many books on firefighting accidents, and son of the late, great Norman Maclean. John was writing a book about an wildland firefighting accident on the Thirtymile Fire, in Washington that killed four firefighters. He had heard I did fire-related mapping work and asked if I’d make the maps. He sent me a manuscript for his new book and I spent several weeks developing illustrations for the story.

This was a challenging assignment. For a wildland firefighter, reading his book is a lot like going through a recurring nightmare. Through a long series of bad calls and miscommunications, you are trapped in a box canyon with a fire burning upstream toward you and no way out.

Artistically, I didn’t know how to treat the terrain or the assignment. I have a hard time feeling good about making a map of a place I’ve never been, and in this case I knew that there would be plenty of eyeballs on this map that had been there on the day that things went down. It was early spring, and the site was under 6 feet of snow, so I never got a chance to see the terrain in person before the maps were due.

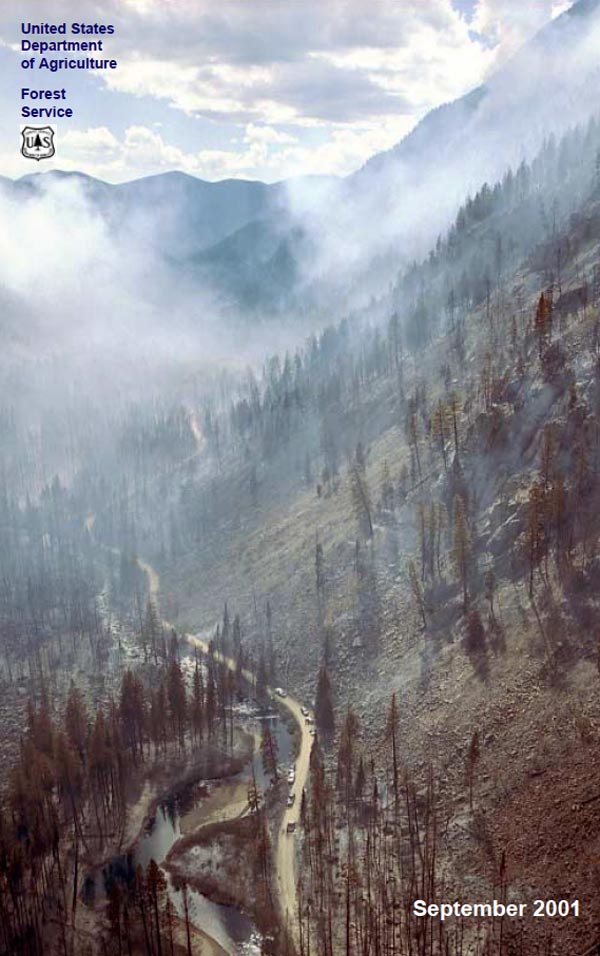

I spent a lot of time talking with my boss at the time – Lonnie Williams, who had been on the fire, had flown it as an aerial observer for days after the tragedy, and who knew many of the players in the story. He had been to the site after the accident, and had walked from the site of the fire ignition up the canyon to the site of the fatalities while the fire was still burning. Lonnie described a steep, rocky, hot, and underestimated landscape that rained hell on those who didn’t recognize just how dry the slopes above them were as they fought fire in the shade near a river.

I spent a lot of time trying to track down the information for the maps. There were still unresolved lawsuits going on 4 years after the accident, and nobody at the Forest Service wanted to talk with me about the story or share information. The District Ranger for the area told me “I don’t talk to anybody about Thirtymile” and hung up the phone.

I filed a Freedom of Information Act request, but even once this was in action, it was hard to track down any usable information. I ended up using some low resolution maps from the official investigation document as my sources, and also information from John Maclean’s interviews. In the end, I got a member of the investigation to sign off on my final map, but still felt uneasy about making a map of a place I hadn’t been.

I decided that either needed the map to be emotionally neutral, with no terrain, just a plain white background, or it needed to have a LOT of emotion, energy, angst, and raw edges.

Waiting for the wheels to turn in Washington I had some time to think about the design and try different materials. I spent a lot of time looking at aerial photos – especially the one above, and I rough sketched the terrain several times before I realized that the map needed that sketch quality, and a wildly scribbled draft became the final. It felt like armchair quarterbacking – not seeing the site, but in the end, I felt like the map captured the quiet raggedness of a place where people could get run over by a wildfire.

Postscript. A year after making the map I was on a fire in Eastern Oregon watching a hotshot crew burn out a grass and timbered slope across the creek from the highway I was on. Their lookout was watching from the same turnout from me, and I noticed that he was from the Entiat Hotshots – a local crew that had been on the fire the day that it blew up. I had a chance to show him a dirty ragged copy of the map that I had in my bag. Here were some of those eyeballs that had seen it go down – quietly, “Yeah, that’s about how it happened”.